How a scented Mediterranean flower ended up bewitching the Far East

[~ 6 minutes]

Listening to: Yoko Kano, Aqua

’Tis said that the sense of smell is intimately connected with memory, something that Proust and his madeleines apparently turned into an incontestable truth.

I am not usually assailed by memories when smelling anything in particular; however, there’s one scent that does trigger a Proustian recollection within me, the scent of a flower that blooms every winter in my parents’ garden: paper whites, or Narcissus tazetta L.

Although narcissus aren’t flowers you’d usually associate with Spain, it turns out that the Iberian peninsula actually boasts the greatest biological diversity of this genus: we have them in all shapes, sizes and colours. The ones I’m familiar with belong to one of the few divisions, the Tazettae, whose members bloom profusely on each flower stalk (instead of producing a single bloom at the tip).

If I had to choose a single word to describe them, if would be fragrant. Their perfume though can be dangerous, or so the ancient Greek myths would have it: some versions of Persephone’s descent into the Underworld featured the narcissus as the sweet-smelling flowers that Hades used to lure the young goddess into his clutches.

Indeed ’tis said that the name narcissus could be related to the Greek root narkao — the same that gave us words such as narcotic. This makes sense when you consider the alkaloid cocktail stored within the plant bulbs, with medicinal/toxic effects that range from severe abdominal pain and vomiting (if eaten), to numbness and eventual heart paralysis (juice extract rubbed into open wounds).

And although there is apparently one species of Narcissus (N. bulbocodium) which you should totally not smell in confined spaces (lest you end up with a headache and vomits), the shadow of danger has spread to the (otherwise innocuous) fragrance of all narcissus, at least in the West… See, for example, what a 19th century perfumery manual has to say about it:

“The smell of it to many is exceedingly grateful, but in close apartments the exhalations of the plant are said to be noxious; indeed, its narcotic odor was known to the ancients, and hence its name is said to be derived from νάρκή, stupor.”

There might be some Persephone-ish gene in me, because I adore the scent of N. tazetta. A different species is used in perfumery (N. poeticus L.); it was once treated via enfleurage and maceration, but nowadays the less poetic —yet more practical— solvent extraction is used to obtain narcissus concrete.

A single kg of narcissus absolute, obtained after processing between 1300 and 1400 kg of flowers, can cost up to 30.000$ per kg.

After a second treatment with alcohol, the final product is obtained: narcissus absolute, apparently one of the most expensive substances in the perfume world.

Nobody knows if scent was the reason that embarked Narcissus tazetta on the greatest adventure that ever befell a daffodil. However, I wouldn’t be surprised if it turned out to be the culprit of this flower’s voyage across the entire Asiatic continent and into the heart of China, where it became associated with river goddesses and happiness-bestowing Taoist genii…

… as well as becoming one of the symbols par excellence of the Chinese New Year.

“Blossoms that make the moon less white”: Narcissus tazetta in China

Its Chinese name, shuixian hua (水仙花), can be literally translated as “water immortal” (shui, water; hua, flower); some of its common names in English are [Chinese] sacred lily or luck lily. It is currently considered a subspecies of my N. tazetta and it goes by the name of N. tazetta subsp chinensis (M.Roem.) Masam. & Yanagih. (although you’ll find it under many different names in the literature… see Note below).

As I already mentioned, despite its popularity as an auspicious New Year flower*, it wasn’t originally Chinese but appears to have been introduced not long before the Song period (960-1279 AD), perhaps via Arab commercial routes; another possibility would be that they arrived as a gift from Italy, of all places!

Be as it may, and bearing in mind that the two main provinces with long-standing narcissus traditions (Fujian and Guangdong) are located on the south-eastern coast of China, I dare say this ‘water fairy’ probably reached the Celestial Empire from the water, too.

Murky origins notwithstanding, this was a flower whose divine fragrance got her some pretty good connections in the supernatural world. Whereas in the West it became symbolically linked to unhealthy self-love (remember the myth of Narcissus?), in the East it came to be associated with grace, purity, happiness and good fortune.

Plus, being a winter-blooming flower, it eventually became one of the plants* linked to the Chinese New Year—so much so that, in order to both predict and ensure that the year will be a happy and prosperous one, your narcissus must be in bloom right when the Lunar New Year begins (which should be the 28th of January 2017 as I write this).

*along with the peach (Prunus persica) and the tangerine (Citrus cf reticulata).

This has led to the development of careful techniques that modulate the growth of your water-fairy flowers; after all, Fortune is too serious a matter to have it depend on a flower’s fickle blooming rhythms. And, unlike what happens with peach and tangerine trees —prepped to perfection by sellers: you simply have to buy them and wait—, the fate of narcissus blossoms also depends on the ministrations of individual buyers.

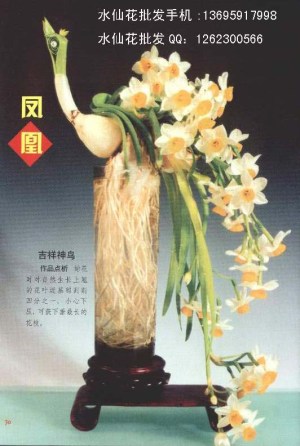

If you want narcissus-inspired Luck to be on your side, you’ll first need a container with clean water and pebbles where you’ll plant your bulbs. You could next leave them alone and wait, but you’re much more likely to work a little magic on them, making delicate cuts in order to coax the plant into adopting a certain shape (what’s known in Chinese as “crab-claws”… although in my opinion they look anything but. They style them in the most fanciful, beautiful shapes, from peacocks to flower baskets… examples can be seen right here , or by copying “水仙花雕刻” on your image search engine of choice).

And after that, do you simply sit down and wait? ‘Course not. You must keep an eye on the bulbs to make sure they bloom exactly when you want them to. Not sooner, not later. In order to control the development speed of your narcissus, you’ll play with:

- Temperature (low temperatures slow the narcissus down, and vice versa);

- Light (which will determine the direction in which your narcissus will put out leaves and blossoms);

- Water (you can dip the stems in sea water to delay flowering; but careful with how you do it, else all buds could fall off).

Carving narcissus into small works of art and cajoling them to bloom at the right moment, if done right, will bring you good fortune for the rest of the year.

Beyond China: Narcissus tazetta in Japan

The story doesn’t end in China, though; because, as it often happens, the flowers that reach the Celestial Empire also reach Japan.

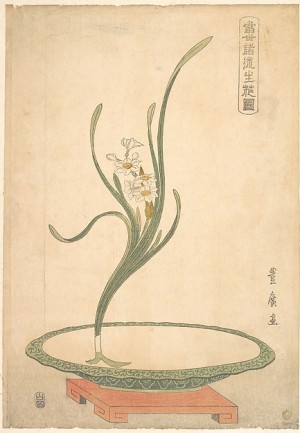

In the land of the rising sun, narcissus (suisen, 水仙) is one of the plants used in ikebana (flower arrangement tradition), where particular attention is paid not so much to the flowers but to the leaves: they must be “taken apart and reconstructed” to achieve the desired effect. It’s a flower often used in arrangements made to accompany and complement the Tea ceremony: they are cha-bana (literally “tea-flowers”).

I haven’t been able to find many scientific papers on Japanese narcissus, yet it appears to be relatively clear that they got there from China after the 1st millennium*.

*some say during the Heian period (794–1185), others the Nara period (710–794 AD)… I’m personally more inclined to say Heian.

Narcissus in Japan aren’t associated as strongly with New Year festivities as they are in China (although there is some connection, according to what’s mentioned here). However, there are annual narcissus festivals (eg. in Fukui province), and particular places famous for their narcissus-strewn fields (eg. Echizen), putting up quite a spectacle when they burst into bloom and carpet the ground in fragrant white.

In Japanese poetry, it is the flower’s exquisite paleness that which is extolled, associated with purity. As a culture that’s finely attuned to the seasons, narcissus also appears in poems that highlight its late-winter blooming, such as the following haiku by Matsuo Bashō:

hatsuyuki ya / suisen no ha no / tawamu made

(Translated as “first snow— / just enough to bend / narcissus leaves”)

All things considered, I’d say that’s quite an astonishing career for such a humble Mediterranean flower.

![]()

So, now you know.

If you are botanically inclined to celebrate the Chinese New Year, N. tazetta subsp chinensis is your best friend.

My garden bulbs bloomed in time for the Gregorian New Year on the 1st of January, but I’m afraid there won’t be many left standing by the end of the month… let’s hope the genii of Good Fortune don’t mind the calendars we live by, as long as our Narcissus are fairly attuned to their rhythms.

{This is an article inspired by an original in Spanish published a while ago, which can be read here}

![]()

Notes on scientific names – profusion&confusion

According to The Plant List, the Chinese sacred lily’s official taxonomic name and status is Narcissus tazetta subsp chinensis. However, I’ve found it referenced under a wide array of names, among which the most common ones are:

- Narcissus tazetta var chinensis M. Roemer, eg in Flora of China (and many other places);

- N. tazetta var orientalis, in Li, H. L. 2002. Chinese Flower Arrangement. Dover Publications: 48-49 (a reprint of the original edition from 1959);

- Narcissus x incomparabilis, in Bernhardt, P. 2008. Gods and goddesses in the garden: Greco-Roman mythology and the scientific names of plants. Rudgers University Press: 61-62.

- Narcissus papyraceus (“various forms of”), in Kingsbury, N. 2013. Daffodil: The remarkable story of the world’s most popular spring flower. Timber Press: 24.

Any time you come across one of these, it’s likely that they’re talking about our Chinese friend, N. tazetta subsp chinensis.

References&Resources

There’s a wealth of information in a book exclusively on the genus Narcissus: Hanks, G. R. (Ed). 2002. Narcissus and Daffodil: The genus Narcissus. Horticulture Research International, Kirton, UK. Taylor & Francis.

The bits of information I quote in the story above that come from this text are:

- The occurrence of the genus Narcissus’ biodiversity centre in the Iberian peninsula;

- Toxic and medicinal effects of the bulbs (and the dangerous scent by N. bulbocodium);

- Origins of the word Narcissus.

One of the chapters is entirely devoted to daffodils in perfumery (Remy, C. ‘17. Narcissus in perfumery’), where you’ll find information on modern methods of flower collection and processing, as well as the weight ratios flowers gathered: narcissus absolute obtained.

The price of narcissus absolute (and a sceptical view on Proustian axioms) comes from Turin, L. 2006. The Secret of Scent: Adventures in Perfume and the Science of Smell. Faber and Faber.

The 19th century perfume manual I quoted was Septimus Piesse’s The Art of Perfumery (…), freely available via Google Books (Lindsay&Blakiston, edition from 1867).

Myths (among which Persephone’s) surrounding the Narcissus, in Cattabiani, A. 2015. Florario: Miti, leggende e simboli di fiori e piante. Mondadori (reprint original edition 1996).

Classic article of Chinese floral symbolism surrounding Narcissus, in Koehn, A. 1952. Chinese Flower Symbolism. Monumenta Nipponica 8 (1/2): 121-146.

Actually, the quote “Blossoms that make the moon less white” is taken from a poem by Yang Wan-li included in the article; the full poem is as follows:

They are wonderfully graceful and fragrant too;

The purity of their blossoms makes the moon less white.

These fairies from Heaven walk not on earth,

So they added “water” to their name.

A description of narcissus as The New Year flower in China, with reference to crab-claw bulbs, in Metcalf, F. P. 1942. Flowers of the Chinese New Year. Arnoldia 2 (1): 1-8.

An introductory summary to Chinese symbolism of narcissus may be found in Eberhard, W. 1986. A Dictionary of Chinese Symbols: Hidden Symbols in Chinese Life and Thought. Routledge: 248-249.

However, the book where I first learnt of the role of Narcissus in Chinese New Year festivities was my beloved copy of Goody, J. 1993. The Culture of Flowers. Oxford University Press: 387-389. It includes the explanations on how to regulate the development of your flowers.

On Japanese narcissus, the website I’ve found with most extensive information on suisen is Amaryllidaceae.org (as Amaryllidaceae is the family to which the genus Narcissus belongs); the webpage where you’ll find the Japanese references is over here.

It also includes though much information on the narcissus in China.

On dates of introduction of narcissus in the East, I’ve found quite a few (although I don’t know how much to trust some of them):

- In Chen, S.-C. and Wu, Y.-X. 1982. Historical notes on Shui Xian—The Chinese sacred lily. [I think it’s in the] Journal of University of Chinese Academy of Sciences 20(3) 371-379. I can only read the paper’s abstract, yet it gives a pretty complete description on the flower’s arrival to China.

- This guy believes narcissus arrived in Japan during the Nara period (710-794 dC), but he never gives proof of why it should be so.

- In amaryllidaceae.org they offer the 12th century (Heian Period) as the introduction date of Narcissus into Japan. I see no reference particularly referred to why it is so, but the bibliography they have on the genus Narcissus is quite impressive… so I trust their data more.

Bashō’s haiku is taken from Landis Barnhill, D. 2004. Bashō’s haiku: selected poems by Matsuo Bashō. State University of New York Press, Albany.

If there’s anything I’ve missed (which is actually quite possible), feel free to drop me a line!

Illustrations

All narcissus photographs are by Yours Truly, most of them taken at my parents’ garden ‘cept for the header one, taken at Barcelona’s Botanic Garden.

The picture of those gorgeous crab-claw narcissus is taken from this Chinese website.

Artworks are taken from:

- The China Museum Online for the Chinese artwork by Qiu Ying.

- The Metropolitan Museum, for the woodblock print by Utagawa; there’s another one featuring an ikebana arrangement here.

Although I haven’t included it here, possibly the most famous eastern painting featuring Narcissus is a Chinese scroll by Zhao Mengjian, which is also in the MET. Well worth checking out, over here.

You can see pictures of a flower market in Hong Kong around New Year (& featuring Narcissus tazetta subsp chinensis, of course) over here.

3 thoughts on “Say it with narcissi: flowers to celebrate the Chinese New Year”